Players

Latest > Representing for all The GolfPunks: Lee Elder

Nov 30th, 2021

Representing for all The GolfPunks: Lee Elder

And his legendary impact on the game

Words: Gavin Newsham Photography: Getty Images

.jpg)

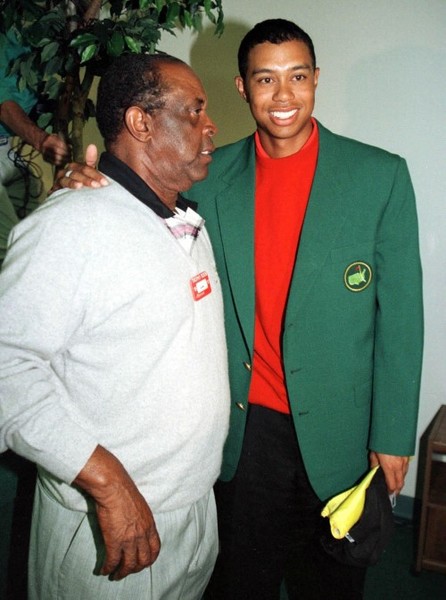

Rising at 7am, he flies to Atlanta before making the two-hour drive to Augusta. Despite being stopped for doing 85mph in a 70mph zone, he arrives just in time to see Tiger Woods rip one down the first fairway – and, some four hours later, slip on the famed green jacket. “I don’t think the world would have been ready to accept a black champion with open arms in my day,” reflected Elder. “In 1975, you needed armed guards to get to the first tee. Today, times have changed. I know he’ll be accepted.”

Tiger Woods has a lot to thank Lee Elder for. Along with Charlie Sifford, Peter Brown and Teddy Rhodes, Elder was one a band of black pioneers who finally brought the PGA Tour to its senses and consigned its Caucasian-only membership clause to its shameful past. And while Sifford gained recognition as the first black player to secure full membership of the PGA Tour, it would be Elder who became the first African-American to play in the notoriously selective Masters tournament.

Born Robert Lee Elder in Dallas, Texas on July 14, 1934, the young Lee took up caddying at the age of nine at Tennison Park Golf Club to help his family out in times of need. By his early teens, it was clear to anybody who watched his fluid swing and his poise over the ball that Elder was a natural. And while he turned professional in 1959, plying his trade on the Black United Golf Association circuit, he would have to wait until 1967 to have his first crack at the PGA Tour’s Qualifying School. Needless to say, he breezed through at the first attempt.

But black players were still treated like second-class citizens in the world of professional golf. Clubhouses were out of bounds, barracking was commonplace and even PGA Tour event winners like Sifford and Brown failed to receive invites to play at the Masters when virtually all the white winners did as a matter of course.

.jpg)

For many, the problem lay with Augusta’s autocratic chairman, Clifford Roberts, a man who had long been seen as the architect and enforcer of the club’s tacit no blacks policy. By the early 1970s, however, the pressure on Roberts and Augusta was mounting and in 1973 he received a letter penned by a group of congressmen demanding a change in policy at the National. Roberts’ response to the letter was typical.

“We are a little surprised as well as being flattered that 18 congressmen should be able to take time out to help us operate a golf tournament,” he wrote. “We feel certain someone has misinformed the distinguished lawmakers because there is not and never has been player discrimination, subtle or otherwise.” This from a man who once said: “As long as I’m alive, golfers will be white and caddies will be black.”

Clifford, though, would be powerless to prevent Lee Elder’s march into golf history. A rule change soon after ensured that every PGA Tour event winner in a given year would be guaranteed an automatic invitation to the following years Masters tournament, so when Elder triumphed in the 1974 Monsanto Open at Pensacola Country Club (a place where he had been refused entry to the clubhouse some six years earlier) his path to Augusta was finally clear. “I didn’t realise how important it was at the time”, he later reflected, because all I really wanted so badly was to play in the tournament.”

But if Elder thought there would be balloons and bunting awaiting him in Georgia, he was wrong. During the week of the Masters, he would receive no less than six death threats. “I was always assured that nothing would happen inside here [Augusta], but I was worried about being outside. It was pretty frightening.”

On April 10, 1975, Lee Elder stepped onto the first tee at Augusta and smacked a beauty straight down the middle. In one shot, after decades of vile abuse and intolerable discrimination, he had finally broken down one of the last remaining barriers in the game of golf. But while he would record three more Tour victories in his career and play on the victorious 1979 US Ryder Cup team, the stench of racism remained in the background.

.jpg)

Even when Elder joined the Seniors Tour, he was still confronted by the kind of ignorance that he might have assumed would have dissipated in the wake of his breakthrough appearance at the Masters. But no. At the Kroger Senior Classic near Cincinnati, for example, Elder finished his round and asked a tournament official if he could get a courtesy car. According to the young woman in charge of the vehicles, there were no cars available. Moments later, however, Elder’s fellow pro, (the Caucasian) Bob Brue appeared and was offered a car immediately. When Brue declined the offer, Elder asked again but still, the woman insisted that there were no cars for him to take.

In his 1992 autobiography Just Let Me Play, Charlie Sifford was still critical of a system that singularly failed to promote or encourage black players in professional golf: “Lee Elder,” he said, “has won over $2 million at golf and was the first black to play in the Masters in 1975. But he never modelled clothes or did an American Express ad or was asked to be a guest commentator on a golf broadcast or was paid $10,000 to appear at some big corporation’s annual golf outing. He was never made a star by the sport, and now that he’s old, he’s just Lee Elder, the first black guy to play in the Masters…."