Players

Latest > Representing: Byron Nelson

May 20th, 2017

Representing: Byron Nelson

GolfPunk's tribute to golf's greatest gentleman

Words: Gavin Newsham Photography: Getty Images

On Tuesday, September 26, 2006, when ‘Lord’ Byron was found dead on the porch of his ranch, golf not only lost one of its brightest and most respected heroes, but also the last remaining link to a bygone era – a Golden Age when Sam Snead, Ben Hogan and Jimmy Demaret vied with Nelson for parity on the burgeoning PGA Tour.

Hoopla! Put that in yer pipes and smoke it, whippersnappers

Hoopla! Put that in yer pipes and smoke it, whippersnappers

Born plain John Byron Nelson Jr – the ‘Lord’ would come later – on his parents ranch in Waxahachie, Texas, on February 4th, 1912, the future Hall of Famer cheated death twice in his formative years. Weighing in at 12lb 8 oz, the sheer size of young Byron added near fatal complications at birth. Then in 1922, shortly after the family relocated to Fort Worth, he contracted Typhoid.

As the fever tore through his immune system, his weight dropped to 65lb his temperature soared to 106 degrees and doctors advised his family that he was near death. Luckily, he survived, and less than three years after fighting a disease with the might to wipe out ancient Athens and the Golden Age of Pericles, he made his first small indent on golfing history.

It’s December, 1927, and the tournament is The Glen Garden Caddy Championship. After enlisting as a caddie in 1924, Byron played his first round of golf in the same tournament that year. Though he shot an undignified 118, he was hooked, and spent the next few years observing the technique of his ‘bags’, and buried in a tattered golf book he found at Fort Worth library. “There were four or five pages in there about Harry Vardon developing his grip,” he said, “he talked about it real well. I sat in there quite a while and learnt how to grip it.”

Scything through the competition, he reached the final against another notable graduate of the Glen Garden caddyshack – Ben Hogan. Following a tight battle, Hogan holed out on the ninth and final hole for a score of 40, and left Byron standing over a 30ft putt to force a play-off. Showing the nerve and composure that would eventually lead to the PGA testing robot being labeled ‘Iron Byron’, he drained the putt and beat Hogan by one shot in the play-off.

Fast-forward to 1932 and Byron is sat on a bus heading for a tournament in Texarkana. After struggling to hold down a job in Depression-era America, he had been scratching a living in temporary work while playing intermittent amateur events.

If you look closely you can just see the pot of gold at the end of the fairway about to be created by Mark McCormack and Arnold Palmer... now, where's that time machine?

Somewhere along the dusty highway, he made the decision to play the tournament as a professional. And after paying the five dollar entry fee, he finished third and left the amateur ranks for good. “I had $75 in my pocket, but still no job. I knew enough, though, to realise that my next step was to go on tour in California that winter, if I could possibly get there.”

1933 found him living back at his parents’ house, broke and unemployed. But then came two decisive breaks. First, he was offered the job of head professional at Texarkana Country Club, which paid him $60 a month. More importantly, though, it gave him vital hours to continue working on a swing that would soon become the prototype for the ‘modern’ era of golfers.

The second break came in the form of a woman. In June, 1933, Byron met a young brunette named Louise Shofner at a local bible class. Louise’s father took such a shine to Byron that he lent him $650 to fund another crack at the professional circuit. After struggling again in California and Phoenix, the tour rolled into Texas.

The two greatest winners ever?

The two greatest winners ever?

Something about the Lone Star State must have awoken Byron and he finished second at San Antonio and Galveston. With $800 in his pocket, he returned to Fort Worth, paid off his future father-in-law, spent $100 on an engagement ring, and never looked back.

With the desperation of the early days behind him, and boasting wins in 1935 and 36, Byron arrived at Augusta National in 1937 in solid form. His swing was beginning to produce consistency over four rounds and he felt ready to make the step up. After shooting an opening 66 – which stood as the best first round until Ray Floyd carded 65 in 1976 – he found himself on Sunday lying three shots behind leader Ralph Guldahl with nine holes to play. What happened next has passed into folklore.

When he wasn't winning golf tournaments, Byron was pioneering the world's living statues movement...

When he wasn't winning golf tournaments, Byron was pioneering the world's living statues movement...

Trusting his swing like never before, Byron took apart the back-nine with ruthless efficiency. He covered Amen Corner in three-under, including an eagle at the par-five 13th, strolled the rest of the course as if playing in a Sunday foursomes, and walked off the 18th with a two-shot victory.

Legendary Atlanta-based sportswriter, O.B ‘Pop’ Keeler, was so moved by the graceful arc of his swing that he compared it to reading a poem, written by Lord Byron, on Byron wins the Masters,’ and a legend was born.

Smooth as silk: You don't win 11 on the bounce by chopping it...

Between this win and the beginning of the 1945 season, Byron won three more major championships. He survived a three-man 36-hole play-off to win the 1939 US Open, beat Sam Snead one-up in the 1940 US PGA and defeated his old Glen Garden sparring partner Ben Hogan over an 18-hole play-off in the 1942 Masters.

With consistency becoming standard, he collected numerous other titles throughout these years, and in a study of many other careers, these achievements would merit more than a mere footnote. But then no other golfer, not Vardon, Nicklaus, Faldo or Woods, has achieved what Byron did in 1945.

Starting the season with a win at The Phoenix Open, he arrived at The Miami International Four-Ball on March 11 in fine fettle, and after winning the event with Harold McSpaden, he found a vein of form so deep he became entrenched in it. Following that win, he beat Sam Snead in an 18-hole play-off at The Charlotte Open.

Fancy a singh songh, errm... Singhy?

Fancy a singh songh, errm... Singhy?

He then won the Opens of Greensboro, Durham and Atlanta to surpass the previous ‘streak’ record of four. Unperturbed by history, he won again at The Montreal Open, and added the Philadelphia Inquirer Invitational and Chicago Victory National Open for good measure. With eight in the bag, he faced his biggest test yet. Until 1957 the USPGA Championship was a Matchplay event, and the rigours of the format could have felled a lesser man. But by coupling form with fight, he beat Gene Sarazen 4&3, rallied from one-down with two to play against Mike Turnesa, and beat Sam Byrd 4&3 in the final after being two-down with eight to play.

Triumvarate Of Legends: Nelson, Sarazen & Snead prepare to start the 1999 Masters

Triumvarate Of Legends: Nelson, Sarazen & Snead prepare to start the 1999 Masters

And when he extended the streak to 11 with wins at the Tam O’ Shanter and Canadian Opens, it seemed that no-one could beat him. Obviously then, someone did. Even though Byron began to close ominously during the final round of The Metropolitan Open, amateur Fred Haas Sr held him off to end the longest winning streak in PGA Tour history. (Tiger stands closest on seven during the 2006-2007 seasons, Ben Hogan is next on six successive wins).

Closing that season with a win at The Glen Garden Country Club, Nelson finished with 18 wins at an average of 68.33 over 112 rounds for the most successful season in PGA Tour history. He also finished runner-up seven times, was never out of the top ten, and at one point played 19 consecutive rounds under 70.

“During his streak, Byron was magical,” recalled Sam Snead some years later. “He had grooved his swing and was happy with it, so he stopped practicing. He would arrive at the course, warm up a bit, hit a dozen balls, a few putts to get comfortable with the speed of the greens, and then go shoot 65!” The season becomes even more remarkable when you consider that he was playing against himself and for his future.

During the Seattle Open, he shot 62, 63, 68 and 66 for a total of 259 that was beaten only once in the next 44 years. “During his streak, Byron was magical,” recalled Sam Snead some years later. “He had grooved his swing and was happy with it, so he stopped practicing. He would arrive at the course, warm up a bit, hit a dozen balls, a few putts to get comfortable with the speed of the greens, and then go shoot 65!” The season becomes even more remarkable when you consider that he was playing against himself and for his future.

I would really get bored. I just decided I was not going to hit one careless shot. “Plus,” he added, “I had the focus of the ranch. Each drive, each iron, each chip, each putt was aimed at the goal of getting that ranch. And each win meant another cow, another acre, another ten acres, another part of that down payment.”

Though he won his first two tournaments of 1946 – and finished the season with six overall – he felt the need for a change. Tired of the road and desperate for the vast confines of his new home, Byron Nelson announced his retirement from professional golf in August 1946. He was 34.

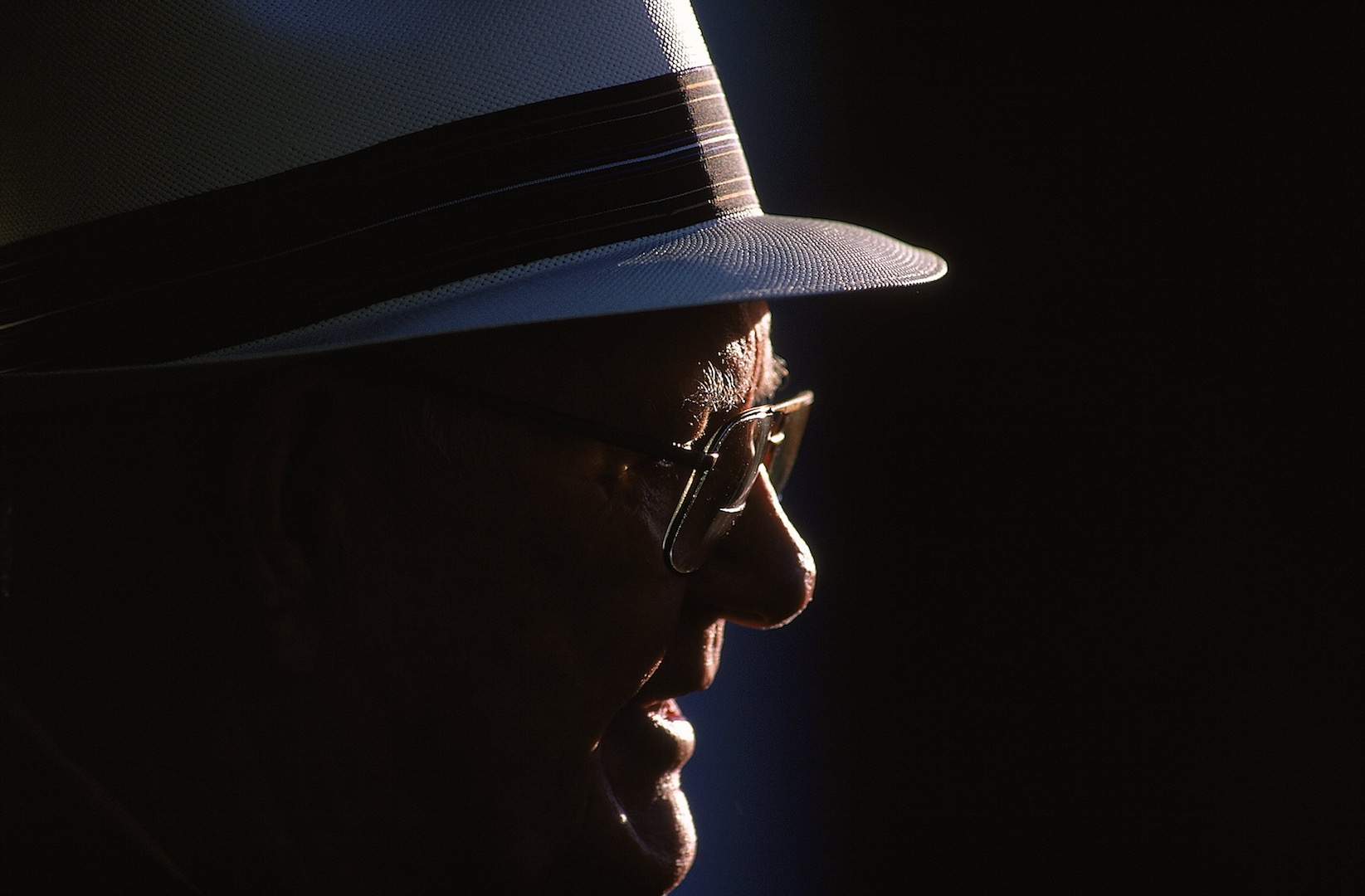

The sun always shines on the righteous

The sun always shines on the righteous

Between 1935 and 1946, Byron won 52 times on tour, with an astonishing 32 of these wins spanning 1944-46. In an era decimated by World War II – he was excused due to his haemophilia – he seized five majors, made 113 consecutive cuts and thrilled galleries with the quality of his game.

He may not have been able to stand the grind any longer, but Byron’s love for golf meant that he continued to play sporadically. He finished second at the 1947 Masters, and played in the triumphant Ryder Cup team of the same year. The ensuing years saw him captain the victorious 1965 Ryder Cup team and become an honorary Masters Starter.

And in a tribute to his 1937 win, the bridge over Rae’s Creek that carries golfers to the 13th green at Augusta is known as ‘Nelson’s Bridge. Always as a keen spotter of talent, Byron mentored both Tom Watson and Ken Venturi and, later in life, he befriended a young Tiger Woods. Active to the last, he even found time to carve wooden keepsakes for the 2006 Ryder Cup team.

For all of his achievements as a golfer, his qualities as a man also assured an enduring love-affair with the American public. In 1968, he gave his name to the struggling Dallas Open. Now known as the EDS Byron Nelson Classic, and with the Lord as a more-than active participant, the tournament has since raised $94 million for charity, and accounts for more than 10 per cent of the PGA Tour’s charitable donations.

The much coveted Byron Nelson Classic trophy

The much coveted Byron Nelson Classic trophy

As an analyst on both CBS and ABC networks, Byron’s kindly face and warm demeanour became a welcoming sight to fans. It is a mark of his humility that he never felt the need to resort to needless criticism.

There have been a handful of sportsmen throughout history whose achievements have equalled Byron’s. But he is surely the only one without a blemish on his character or a bad word said against him.

“I am more pleased of my reputation than of all the tournaments I won,” he said in 1993.

So when, on September 26, ‘Lord’ Byron Nelson closed his eyes for the last time, golf and humanity suffered a huge loss. His achievements need no comparison or justification, and it is an exercise in futility trying to place him in the pantheon. Not only was ‘Lord’ a prince among men, he had the most successful season in the history of professional golf. And considering the players that have ruled since, that should be more than enough.

Related to this story:

Representing: The Slammer Sam Snead and his remarkable life

Representing: How Charlie Sifford revolutionised modern golf

Representing: Max Faulkner - 50 cigarettes a day and little practice = superstar

Representing: Gary Player asks us to punch him in the stomach!

Representing: Dai Rees, the legendary Welsh Ryder Cup hero

Representing: How Bernard Gallacher went from Wentworth pro to Ryder Cup legend

Representing: JH Taylor - along with James Braid & Harry Vardon, one part of The Great Triumvarate

Representing: Lee Elder takes up the Charlie Sifford mantle

Most wins in a single PGA season

18

Byron Nelson, 1945

13

Ben Hogan, 1946

11

Sam Snead, 1950